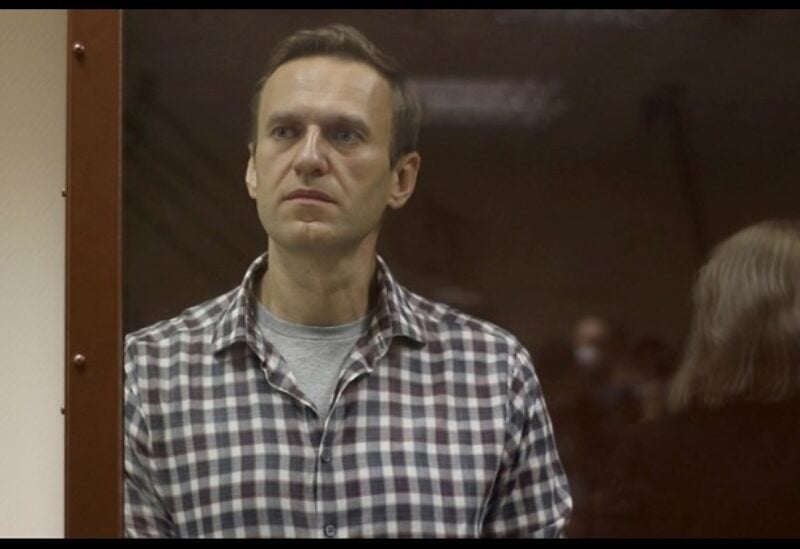

navalni

The coronavirus pandemic has had wide-ranging effects around the world, at both the individual and collective level. But over a year into the pandemic, the ways in which government responses to it have altered society are becoming more clear. The latest report from the Council of Europe offered a stark assessment:

“2020 has been a disastrous year for human rights in Europe. While, increasingly, commitment to upholding human rights standards has been faltering all over the continent for several years, the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the erosion of the democratic fabric of our society, on which protection of human rights ultimately depends.”

This unusually stark language hailed from the office of Commissioner for Human Rights Dunja Mijatovic, which late last year issued the report. In it, the commissioner not only painted a dire picture of the authoritarian trend among Europe’s governments but also pointed to the failure of European institutions both at a regional level and as international agents to effectively buck the trend.

The assessment was echoed in still more dramatic terms by Marija Pejcinovic Buric, the secretary-general of the body in May: “In many cases, the problems we are seeing predate the coronavirus pandemic but there is no doubt that legitimate actions taken by national authorities in response to COVID-19 have compounded the situation. The danger is that our democratic culture will not fully recover.”

Mijatovic spoke with Conflict Zone host Tim Sebastian about the high-profile case of Alexi Navalny, the Russian opposition leader, who was hospitalized in Germany after a reported poisoning and then imprisoned immediately upon his return to Russia. Sebastian noted that the Kremlin had clearly flouted the orders of the European Court of Human Rights, and asked where that left Mijatovic’s body, given that despite being a member state of the Court, “Russia’s justice minister called the ruling enforceable and threw it in the bin.”

The commissioner referred to the events as “a clear disregard of human rights and international obligations,” saying that the Navalny case is an “emblematic case.” The situation also “shows that beneath [it] there are many more problems like lack of independent judiciary in Russia, human rights abuses in Chechnya, lack of investigation, repression of dissent and harassment of human rights defenders. So it’s not just Navalny.” Mijatovic said the case was just one example of “where we see that Russian Federation is completely disregarding the decision of the European Court of Human Rights. But I still remain hopeful that he will be soon free and Russia will show that they are [an] important member of the Council of Europe. This is unacceptable and it has to change.”

The Council of Europe, which is the oldest political body in the continent and precedes the creation of the European Union by almost half a decade, includes among its members all nations of the continent with the exception of Belarus, Kazakhstan and the Vatican City. But the Council has had only limited success in persuading governments to stick to the commitments they took in joining the body and often have appeared as a lonely voice speaking into the void.

The implementation of recommendations and rulings by the European Court of Human Rights, which are binding according to treaty, is left to the discretion of the individual nations; thus by virtue of its setup, the body’s power of enforcement is very limited, a weak point that the Bosnian rights advocate addressed in the interview. “I cannot change the governments. I cannot play to be in opposition, but I can use something that is the most, I would say, powerful tool in my toolbox as commissioner, which is my voice,” said Mijatovic.

But words have hardly done much to defend human rights across the continent; Council of Europe member states have entirely disregarded 45% of finalized cases with fixed rulings demanding the redress of human rights violations and have faced little consequences if any at all. Governments which have seen major lapses in democratic rules and rights such as Turkey, Hungary, Poland, Slovenia and Russia have found no effective pushback.

Asked by Sebastian about this concerning trend, Mijatovic explained that public pressure on those states must continue, from the public and from fellow governments. “Not executing judgments of the European Court of Human Rights is unacceptable. And all the countries that are really not doing it should be called [out] publicly,” the commissioner said.