The World Bank expects the MENA region to fall below the absolute water scarcity threshold of 500 cubic meters per person per year. (Asharq Al-Awsat)

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region is going to face unprecedented water scarcity in the future, warned the World Bank.

In a report, titled “The Economics of Water Scarcity in the Middle East and North Africa Region – Institutional Solutions,” it indicated that by 2030, the water available per capita annually in the MENA would fall below the absolute water scarcity threshold of 500 cubic meters per person per year.

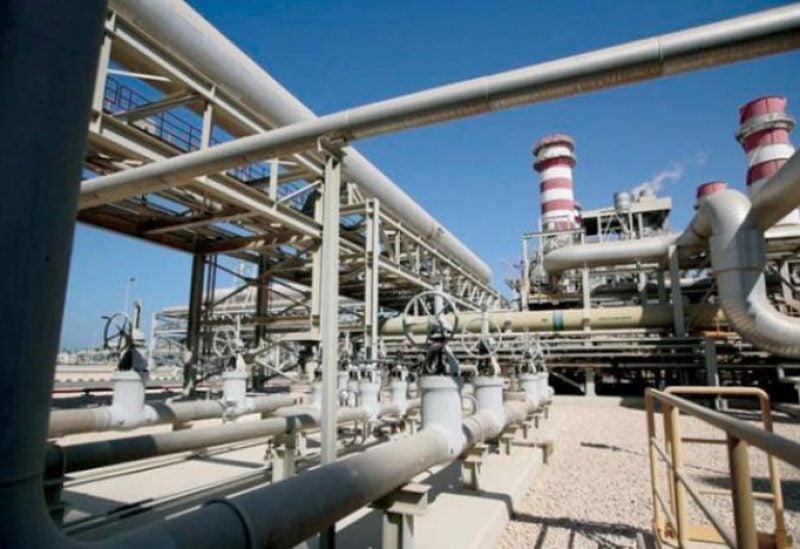

With current water management strategies, a conservative estimate of water demand in 2050 is that an additional 25 billion cubic meters a year will be needed, equivalent to building 65 desalination plants the size of the Ras al-Khair plant in Saudi Arabia.

According to the report, existing institutions that manage water allocation across competing needs, particularly between agriculture and cities, were highly centralized and technocratic, limiting their ability to resolve tradeoffs in water use at the local level.

The report indicates that devolving greater powers over water allocation decisions to locally representative governments within a national water strategy could lend legitimacy to difficult tradeoffs in water use compared to top-down directives from central ministries.

World Bank Vice President for the MENA Region Ferid Belhaj warned that water shortages severely challenge both lives and livelihoods as farmers and cities compete for this precious natural resource and stretch water systems.

“A new approach is needed to tackle this challenge, including delegating more control to local authorities on how water is allocated and managed,” added Belhaj, who joined an event in Rabat to launch the new report.

Countries across the MENA have invested heavily in new infrastructure, such as dam storage. Still, they found ways to tap into extensive groundwater resources and increased virtual water imports by bringing in water-demanding grains and other products from outside the region.

The approach increased agricultural production and access to water supply and sanitation services in cities.

The report argues that this expansionist approach to water development now faces limits that require countries to make difficult tradeoffs.

The report stated that opportunities to expand water storage capacity have plateaued, groundwater is being over-exploited with negative consequences on water quality, and importing virtual water has left countries open to global shocks.

Compared to past investment in dam storage and groundwater, the costs of investing in non-conventional water sources – such as seawater desalination and wastewater reuse – is much higher, which will further strain countries’ finances, the report said.

To maximize opportunities for climate finance and global financial markets, the report said that countries across the MENA must build institutions convincing those markets that governments can raise revenues to service debt.

World Bank Chief Economist for the MENA Roberta Gatti noted that giving greater autonomy to utilities to reach out to customers regarding tariff changes could also win greater compliance with tariff structures, lowering the risk of protests and public unrest over water.

Gatti stated: “These kinds of reforms could help governments to renegotiate the social contract with the people of the MENA and build greater trust in the state to manage water scarcity.”

For institutional reforms to succeed, the report encourages clear communications around water scarcity and national water strategies, explaining to communities why certain decisions are taken.

The approach helped in countries like Brazil and South Africa, where strategic communications efforts complemented reforms to reduce water use during times of great scarcity.