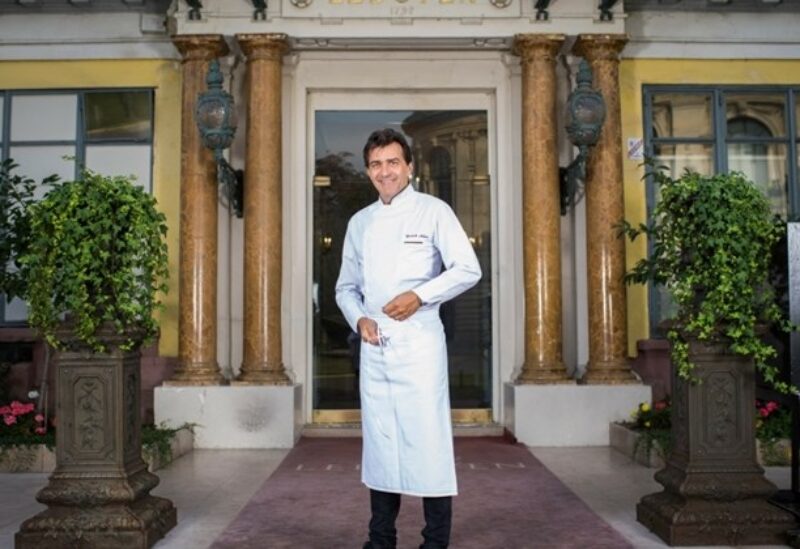

Three stars chef Yannick Alleno poses in front of his restaurant Le Pavillon Ledoyen in Paris.

Davide Sanna, like many young Sardinian people growing up, had a passion for Italian food and aspired to become a successful chef. But he had to relocate to New York to do this.

Beginning when he was just nineteen, Sanna had spent four years working in kitchens on the Mediterranean island and in northern Italy. However, he was working sixty hours a week for, at most, 1,800 euros ($1,963.26) per month. He would spend two months, nonstop, at the stove during the hectic summer months.

Then a fellow chef put him in contact with a restauranteur looking for cooks in New York, Sanna said. He accepted without giving it a second thought.

For the past year, the 25-year-old has cooked at Piccola Cucina, an Italian restaurant in Manhattan’s glitzy SoHo district, home to designer boutiques and high-end art galleries. In New York, he can pull down $7,000 a month, working a 50-hour week.

“Here there are regular contracts, nothing in the ‘black’,” said Sanna, using the Italian slang for undeclared labour. “And, if you work a minute extra, you’re paid for it. It’s not like that in Italy.”

Italy’s food is famous the world over but many talented young chefs, hoping to make a career in their country, find themselves frustrated by low pay, lack of labour protection and scant prospects. Since the launch of Europe’s single currency 25 years ago, Italy has been the euro zone’s most sluggish economy.